Lipid bilayers - Part II: Complex mixtures

In case of issues, please contact Luís Borges-Araújo or Manuel N. Melo.

Summary

Introduction

When setting up large and/or complex bilayers it can be more convenient, or necessary, to start with a bilayer close to equilibrium rather than trying to get the bilayer to self-assemble. This can be done by concatenating (e.g., using gmx genconf) and/or altering previously formed bilayers, but an easier approach is to use a bilayer formation program such as Insane[1] (available from the Downloads -> Tools section of the website, as pip install --user insane, or from its GitHub repo).

Note: Because very recent (as of writing) lipid parameters will be employed, the latest

Insaneversion from the GitHub repo will be used.

Note: This tutorial assumes you are familiar with running Martini 3 simulations with GROMACS, and with the organization of the particle and molecule topologies bundled with the Martini 3 release. For a lipid-centered primer on these topics you can run the Lipid Bilayers I tutorial. Additionally, depending on the version of

insaneyou run, and on whether you run the supplied analyses, you will need to have installed thenumpyandMDAnalysisPython packages. If needed, you can typically install them viapipby runningpip3 install --user numpy mdanalysis.

Complex mixtures with Insane

Insane (INSert membrANE) is a CG building tool that generates membranes by distributing lipids over a grid. Lipid structures are derived from simple template definitions. Many are already included with the program (see below on how to add new ones). The program uses two grids, one for the inner and one for the outer leaflet, and distributes the lipids randomly over the grid cells with numbers according to the relative quantities specified. This allows for building asymmetric bilayers with specific lipid compositions. The program also allows for adding solvent and ions, using a similar grid protocol to distribute them over a 3D grid. Finally, the Insane script can also be used to set up a complex (or simple!) bilayer system including membrane proteins. Additional information about the functionality of Insane can be found by running insane -h.

COBY

While Insane is the most widely used tool for membrane building in Martini (and the one used in this tutorial), an alternative is COBY. COBY is a Python-based tool for building flat coarse-grained membranes, supporting asymmetric and phase-separated systems, multiple bilayers, protein insertion, solvation, and solvation with one or more chosen solutes. Versatile and highly customizable, it is particularly well-suited for more complex system setups; however, it is outside the scope of this tutorial. More information, including features and example systems, can be found on the COBY GitHub repository.

Because Insane deals mostly with structure generation, it can be used for both Martini 2 and 3 lipids, to the extent that they keep the same number of beads and mapping. However, beware that this may not be always true for future Martini 3 lipid models. Conversely, not all the lipid types you’ll find available in Insane have been implemented in Martini 3.

As with other tutorials, this one offers a worked version with all the intermediate steps bilayer-lipidome-tutorial-II_worked.tgz, and a bare one, that expects you to do and simulate more bilayer-lipidome-tutorial-II_minimal.tgz. Unpack the tutorial’s archive and enter the subdirectory bilayer-lipidome-tutorial-II/minimal/complex-bilayers/ or bilayer-lipidome-tutorial-II/worked/complex-bilayers/.

We will create with Insane a fully hydrated 2:1 mole ratio bilayer of dibehenoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DBPC) : dilinoleyl-phosphatidylcholine (DLPC), with physiological ion concentrations. DBPC has long saturated chains (22:0), whereas DLPC’s are shorter and polyunsaturated (18:2). Because of its saturation, DBPC has a gel-to-liquid transition temperature of 348 K; DLPC’s transition occurs at 216 K[2]. By simulating a mixture of these lipids at an intermediate temperature, we can expect the formation of two coexisting phases: a gel one enriched in DBPC, and a liquid one enriched in DLPC. In this tutorial we will be running a simulation at 290K, using DBPC and DLPC as opposite extremes to ensure a successful separation.

Note: The initial Martini 3 lipid parameters were not always able to correctly reproduce this sort of phase separation when lipid transition temperatures were closer together. However, the lipid parameters were updated and greatly expanded in 2025[3] and such phase separation is now attainable. This tutorial uses the updated parameters, but still focuses on the DBPC:DLPC extremes to allow for meaningful results in a shorter simulation time.

As of writing, the PyPi Insane releases do not yet work with the updated Martini 3 lipid parameters. We will therefore employ the latest version from the Insane GitHub repo. Still, this version does not know the details of DLPC, which we will supplement.

Start by installing the latest Insane, using pip from its GitHub repo:

pip install --force-reinstall --no-deps simopt git+https://github.com/Tsjerk/Insane.gitThen download the Martini 3 particle definitions and solvent/ion topologies, as well as the required .itp files for the updated lipid parameters:

wget https://cgmartini-library.s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/1_Downloads/ff_parameters/martini3/martini_v300.zip

unzip martini_v300.zip -x __MACOSX/* */.DS_Store

cp martini_v300/martini_v3.0.0.itp martini_v300/martini_v3.0.0_ions_v1.itp martini_v300/martini_v3.0.0_solvents_v1.itp .

wget https://github.com/Martini-Force-Field-Initiative/M3-Lipid-Parameters/raw/refs/heads/main/ITPs/martini_v3.0.0_ffbonded_v2.itp

wget https://github.com/Martini-Force-Field-Initiative/M3-Lipid-Parameters/raw/refs/heads/main/ITPs/martini_v3.0.0_phospholipids_PC_v2.itpThe custom Insane has settings for DBPC but not DLPC. It accepts a number of flags with which you can specify a new lipid (the -al* flags; read more with -h). Unfortunately, a bug causes Insane to mislabel tail bead names of added lipids. As an alternative way to correctly add a lipid definition to Insane, we will directly edit its database (this will be also be useful for the exercise ahead when we’ll add a new lipid type). First we must find the Insane installation directory by running:

python3 -c 'import insane; print(insane.__path__[0])'In that directory look for the file lipids.dat. Edit it and find the section of [ diacylglycerol ]. Add the following line to that list of lipids (order won’t matter, but it makes sense to put it next to other PC lipids):

M3.DLPC 0 - - - NC3 - PO4 GL1 GL2 C1A D2A D3A C4A - - C1B D2B D3B C4B - -You can then run Insane to build the starting membrane:

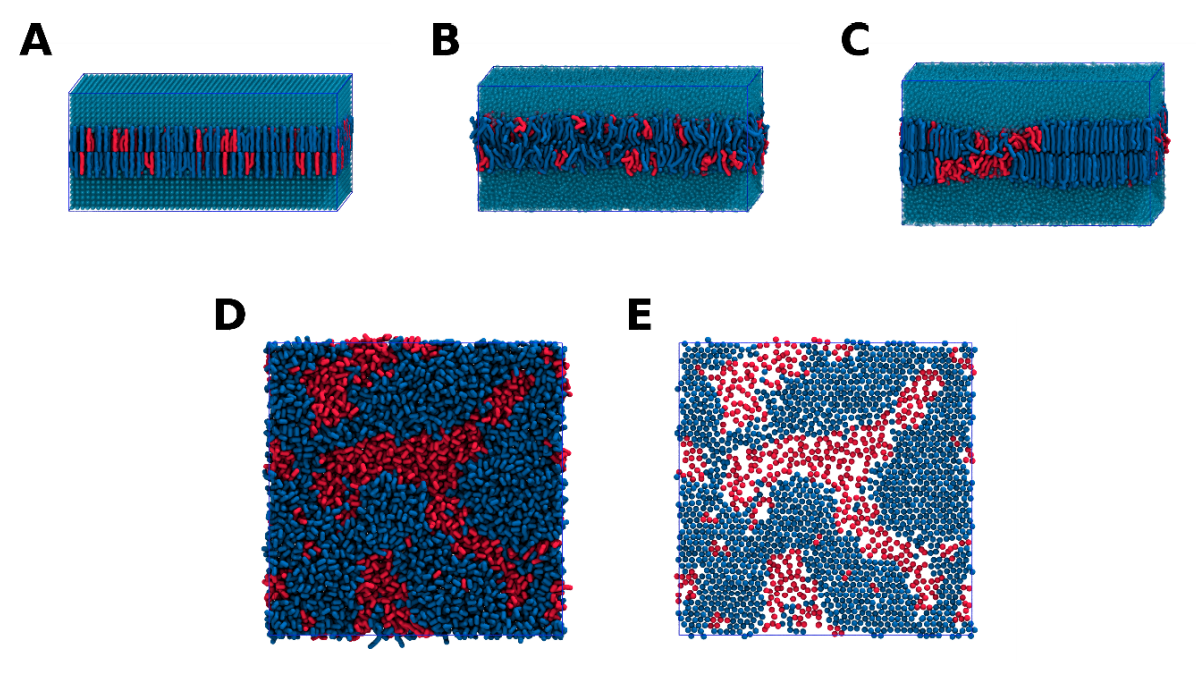

insane -salt 0.15 -x 20 -y 10 -z 10 -sol W -o membrane.gro -l DBPC:2 -l DLPC:1 -p topol.topThis will generate an initial configuration for the system membrane.gro (Fig. 1A) and a starting point for a working topology topol.top, which you must complete and correct:

- It may have an include referring to a generic

martini.itp(it should instead point tomartini_v3.0.0.itp); - You must also

#includethe downloadedmartini_v3.0.0_ffbonded_v2.itpandmartini_v3.0.0_phospholipids_PC_v2.itp(in this order, but aftermartini_v3.0.0.itp).

Then, energy-minimize the structure using the provided em.mdp file.

After minimization we directly run a production simulation at 20 fs time step (with md.mdp). Skipping direclty to production is possible because, since GROMACS 2021 and the introduction of the the C-rescale barostat, pressure/temperature schemes are the same for pressure/temperature equilibration and for subsequent production. We must bear in mind that during the initial nanoseconds of this run, the grid order imposed by Insane (Fig. 1A) will still be relaxing (Fig. 1B), as will the pressure and temperature. Also, because this simulation contains multiple components you will have to make an index file (using gmx make_ndx) and group all the lipids together and all the solvent (water and ions) together to fit the specified groups in the .mdp files; the provided .mdp files expect the index group names Bilayer and Solvent.

This DBPC:DLPC mixture separates in a couple hundred ns at a temperature of 290 K (Fig. 1C,D,E). If you don’t want to wait that long for your simulation, a sample run is provided for you under phase_sep.xtc (if you’re not using the ‘worked’ tutorial files, you can get it from here, as well as a compatible phase_sep.tpr from here). If you do run the simulation, take the time to revisit Insane’s lipids.dat and understand its structure.

Note: As

Insaneplaces lipids and solvent on a grid, they can still be in an energetically unfavorable state even after minimization. Due to the large forces involved it is sometimes (but not always) necessary to run a few equilibrium simulations using a short time step (1-10 fs) before running production simulations at the standard 20-fs Martini time step. The lipids used in this exercise should not require such intermediate equilibration.

If you have VMD installed and name your .tpr file and output trajectory phase_sep.tpr, phase_sep.xtc, respectively (hint: pass the -deffnm phase_sep flag to gmx mdrun, or rename the files after the simulation), you can load a visualization similar to that in Fig. 1 by running the do_vmd.sh script. Note that that visualization has several representations that are hidden (text in red) and that can be enabled by double-clcking on them.

Insane B) After energy minimization and 500 ps of simulation the grid structure is no longer visible. C,D,E) After 200 ns at 290 K this lipid mixture has phase separated into ld and so domains; D and E show the top view of the simulation, and in E only the first bead of each acyl tail of the top leaflet is represented, highlighting the gel-phase hexagonal packing (VMD’s use of multi-frame position averaging further highlights the honeycomb pattern). In all panels DBPC is in blue and DLPC in red.Analysis — hexagonality

This system can be subjected to several types of analysis (see the Lipid Bilayers I tutorial for general examples). Some specific analyses can be used to characterize this phase separation. Namely, those that look at lipid order and contacts (sadly, the do_order script you may have used in the Lipid Bilayers I tutorial is not compatible with lipid mixtures). Here we’ll quantify the ‘hexagonality’ of the lipid tail packing along the phase transition. In this measurement, that looks only at the tails’ first beads (see Fig 1B to understand why), a lipid tail is said to be hexagonally packed if:

- its first bead has at least 6 neighboring beads within 6 Å;

- all of its 6 closest neighbors have themselves at least 2 neighbors within 6 Å.

These criteria may yield some false positives and some false negatives, but are simple enough for this application (beware that different studies may employ different criteria for hexagonality). The script hexagonality.py computes this for you, for every frame, and outputs a hexagonality.xvg that you can quickly plot with xmgrace. Make the script executable, if needed, and run it:

./hexagonality.py -f phase_sep.xtc -s phase_sep.tpr

xmgrace hexagonality.xvgAppreciate the quantitative view of the degree of phase separation / gel formation along time. Does the fraction of hexagonally packed tails match your expectation given that DBPC makes up two-thirds of this system?

You have now prepared, simulated and analyzed a phase-separating binary mixture of DLPC and DBPC lipids. Molecular simulations have a limited numerical accuracy, and this can sometimes create temperature imbalances — particularly in phase-separating systems[4]. As an extra step, it would be wise to also check the temperature of the separated parts and see if there are any imbalances limiting or exacerbating the phase separation.

Adding a new lipid headgroup: lysyl-PG

When working with complex lipid bilayer systems, you might find that your lipid of interest is not yet available in the Martini lipidome. If so, it might be necessary for you to parameterize a lipid headgroup yourself. In this part of the tutorial, we will outline how new lipid headgroups can be parameterized and leveraged to create complex bilayer systems, using Lysyl-PG as an example.

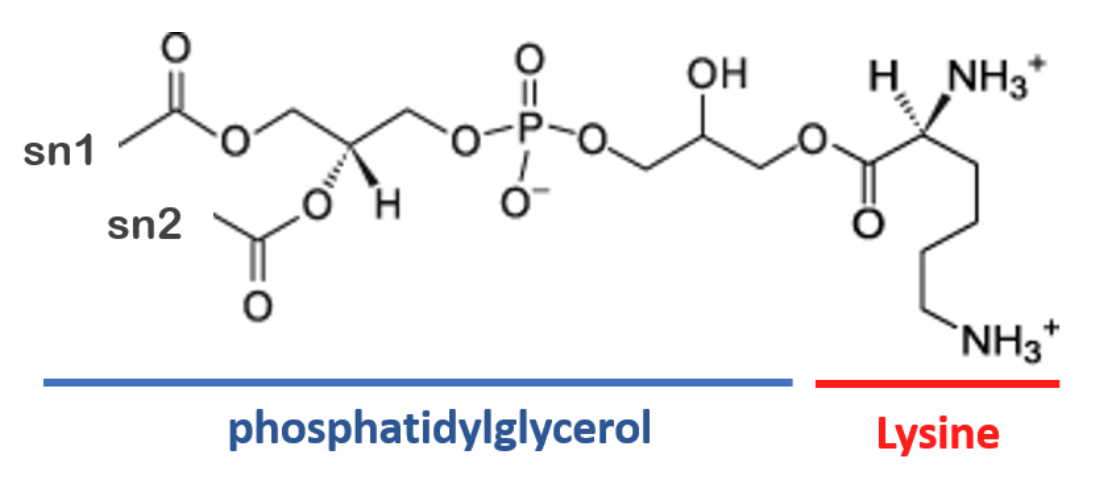

Lysyl-PG (lysyl-phosphatidylglycerol) is a membrane lipid in several gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, which confers a higher level of antimicrobial resistance to cationic host defense peptides[5]. Lysyl-PG consists of the ester of phosphatidylglycerol (PG) with the amino acid lysine (Fig 2). However, even though the lysine and PG topologies are available for Martini 3, there is no conjugated lysyl-PG topology yet.

Creating the lysyl-PG topology

Enter the directory new-headgroup/ within the tutorial’s archive. Start by obtaining the Martini 3 topology files (either from the directory of the previous exercise or by re-downloading their archive and unziping it). You must also download the .itp file with the updated lipid parameters for PG:

wget https://github.com/Martini-Force-Field-Initiative/M3-Lipid-Parameters/raw/refs/heads/main/ITPs/martini_v3.0.0_phospholipids_PG_v2.itpTo create the lysyl-PG topology, we will combine the pre-existing Martini 3 topologies of lysine and of the POPG lipid. We will employ a simple conjugation, assuming a bond between the amino acid backbone (BB) and the PG glycerol (GL0) with the same characteristics as the phosphate – glycerol bond (PO4 -- GL0) already in place. Find the topology for POPG within the Martini 3 PG phospholipid topologies (martini_v3.0.0_phospholipids_PG_v2.itp), as well as the topology for lysine within the Martini 3 amino acid topology file (martini_v300/martini_v3.0.0_proteins/force_fields/martini3001/aminoacids.ff). Create a new file named lysylPG.itp and copy over the two topologies. Note that the topology in martini_v300/martini_v3.0.0_proteins/force_fields/martini3001/aminoacids.ff is in the format of the Vermouth software, which is slightly different from that of GROMACS (for instance, $prot_default_bb_type is a macro that is replaced by P2).

Take a moment to look at the two topologies. These two must now be combined onto a single one, taking care not to break any of the bonded parameters already in place. The simplest way of doing this is by using the POPG topology as a template and adding the lysine parameters on top. As such, start by renaming the molecule by changing the name in the [ moleculetype ] section to POLPG. We can then start merging the [ atoms ] section by adding the list of lysine atoms/beads to the top of the POPG atoms already in place. Care must now be taken to correctly renumber all of the atom entries as well as to change the residue names to POLPG.

Initially, your [ moleculetype ] and [ atoms ] sections should look something like this:

[ moleculetype ]

; molname nrexcl

POLPG 1

[ atoms ]

; id type resnr residu atom cgnr charge

1 P2 1 POLPG BB 1 0 ;Lysine

2 SC3 1 POLPG SC1 2 0

3 SQ4p 1 POLPG SC2 3 1.0

4 P4r 1 POLPG GL0 4 0 ;POPG

5 Q5 1 POLPG PO4 5 -1.0

6 SN4a 1 POLPG GL1 6 0

7 SN4a 1 POLPG GL2 7 0

8 C1 1 POLPG C1A 8 0

(continues ...)Now take a look at the bonded parameters in place in the [ bonds ] and [ angles ] sections. Notice that since we renumbered the atom list, the POPG bonded parameters no longer correspond to the correct atoms/beads. To fix this we simply need to update the numbering on the bonded potentials to the current bead numbers:

The previous harmonic bond definition:

[ bonds ]

(...)

1 2 b_GL0_PO4_def

(...)After renumbering it will now be:

[ bonds ]

(...)

4 5 b_GL0_PO4_def

(...)(note the use of macros representing the lipid bonded parameters; these macros are defined in martini_v3.0.0_ffbonded_v2.itp. Macros can be used in the same .itp alongside numerical parameters, such as those for the lysine bonds/angles.)

Renumber the POPG bonded parameters in the [ bonds ] and [ angles ] sections. After you’ve done this we can now add the lysine bonded parameters. The lysine topology contains 2 bonds and 1 angle potential. Since we added the lysine atoms/beads first in the [ atoms ] section we can simply add those to the list without needing to renumber them.

At this point we will now have the two topologies fully merged, however, the lysine and POPG moieties are not yet connected together! To connect them we must add an additional bonded potential, linking the POPG glycerol (GL0) to the lysine backbone (BB). To do this we will assume that the bond in place is similar to the PO4 -- GL0 in place. As such, create a new bonded potential linking the GL0 and BB beads with the same potential as that of the PO4 -- GL0 bond. Note that now that the glycerol group of the PG moiety is forming an ester bond with the lysine backbone, the chemical properties of the GL0 bead will be different from those when it was free. As such, we must change the bead type to account for the decrease in polarity from the loss of the hydroxyl group. Taking other Martini 3 models as examples, and with inspiration from the “Martini 3.0 Bible”[6] we can tentatively lower the GL0 bead’s polarity from P4r polarity to P1. Additionally, the lysyl BB bead should behave as having a protonated NH3+ group, which warrants changing its type from P2 to Q5 and setting its charge to +1. The lysyl-PG topology is now complete.

Note that this was a “coarse” approach to the parameterization of a lipid headgroup, where some assumptions were made for the sake of simplicity and brevity (e.g. assuming the

GL0 -- BBester bond behaves as thePO4 -- GL0bond, assuming lysine conformation dynamics remain the same when bonded to POPG, assuming the modified glycerol moiety is correctly represented by a P1 bead, etc.). However, this model could serve as a starting point for the refinement of a finer, more accurate model, focusing on the linkage details: bonds, angles, and dihedrals, as well as a finer tuning of the glycerol bead particle type. Refinements of lipid models typically use atomistic MD models of the same lipid as reference for their conformational dynamics[3]. Additionally, other theoretical or experimental parameters are also used as reference targets, such as area per lipid, membrane thickness, etc. Refer to the tutorials on small molecule parameterization where some of these aspects are tackled in more detail.

Adding lysyl-PG to Insane

Having created a topology for lysyl-PG we now want to incorporate it in bilayers assembled by Insane. However, since this is a new lipid topology, there are no available templates for our lysyl-PG lipid in insane, and we must define it ourselves.

Lipids in Insane are defined schematically, based on templates. These templates roughly define the x,y,z pseudocoordinates for each of the CG beads. Adding a new template to Insane is as simple as defining the position of each of the lipid beads in this pseudocoordinate system. Due to its smooth energy landscape, Martini is quite robust and much more tolerant to distortions of the starting structures than, for example, atomistic simulations. This allows us to construct complex membranes from very simple lipid templates. (See the Insane publication for more details[1].) While different versions of Insane have slightly different template formatting, the overall approach is very similar.

Use your text editor of choice to open the lipids.dat file under the Insane python installation directory (as done above). Look for the [ diacylglycerol ] template and the DPPC definition:

[ diacylglycerol ]

;

; PROTOLIPID (diacylglycerol), 18 beads

;

; 1-3-4-6-7--9-10-11-12-13-14

; \| |/ |

; 2 5 8-15-16-17-18-19-20

;

0 .5 0 0 .5 0 0 .5 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

10 9 9 8 8 7 6 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 5 4 3 2 1 0

; 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

; Martini 3 types

(...)

M3.DPPC 0 - - - NC3 - PO4 GL1 GL2 C1A C2A C3A C4A - - C1B C2B C3B C4B - -

(...)A lipid template is defined by setting the relative x,y,z pseudocoordinates for each of the particles in the pseudotemplate in lipidsx, lipidsy and lipidsz, respectively (these are the three non-comment lines immediately after [ diacylglycerol ]). Each lipid entry will then populate the particles in the template as required. If you scroll around lipids.dat you will notice that some families of lipids will have their own templates, such as glycolipids or cardiolipins.

The order in which the atoms are defined in the topology matters when defining the lipid template. While lipid atoms in Martini are typically roughly ordered from top to bottom (outermost headgroup bead to innermost acyl chain bead) this may not always be the case (e.g. phosphoinositol phosphates are defined after the headgroup sugar ring when they are typically the outermost beads). This is also the case with our lysyl-PG topology, where the backbone bead (BB) is defined before the most superficial SC2 bead. While we could re-order and adapt our topology to fit one of the pre-existing templates, we will create our own template specific to lysyl-PG.

Start by drawing out the template for lysyl-PG, using the [ diacylglycerol ] template as a guide. If you are struggling with visualizing the structure, pen and paper are your friends! Having drawn the template, assign x,y,z pseudocoordinates for each of the beads, based on the preexisting templates. In our case, every bead from the phosphate bead (PO4) down should match the default diacylglycerol template. Do not pay too much attention to the precise distances between beads since, as it was previously mentioned, Martini is quite robust in handling rough starting conformations. Distances of 0.5 or 1 between beads are typical.

While it is worth noting that there are many valid templates, in the end, your lysyl-PG template should look something like this (note the difference in z-positions relative to the existing diacylglycerol template):

[ lysylpg ]

;

; PROTOLIPID (lysyl-phosphatidylglycerol)

;

; 3 1--4--5--6--8--9--10--11--12--13 SC2 BB--GL0--PO4--GL1--C1A--(...)

; \ | \ | \ | \ |

; 2 7--14--15--16--17--18--19 SC1 GL2--C1B--(...)

;

0 .5 0 0 0 0 .5 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

9 9 10 8 7 6 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 5 4 3 2 1 0

; bead number: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

M3.POLPG 1 BB SC1 SC2 GL0 PO4 GL1 GL2 C1A D2A C3A C4A - - C1B C2B C3B C4B - -

; M3 indicates this template will be used when the Martini 3 FF is asked for (which is the default)

; The numeric '1' field is the lipid's overall chargeIf you’ve correctly added this entry to lipids.dat, you should now be able to assemble membranes containing lysyl-PG. Try assembling a membrane composed of 5:1 POPG:POLPG using Insane:

insane -salt 0.15 -l POPG:5 -l POLPG:1 -x 20 -y 10 -z 10 -sol W -charge auto -sol W -o membrane.gro -p topol.topUse it as a starting point to run a simulation with this membrane mixture, following the steps above (set the temperature to 300 K and total run time to 50 ns). Because we specify the lipid’s charge in the lipids.dat database, we can use Insane’s -salt and -charge flags to set ionic strength and system neutralization in one go.

You now have a topology for a custom lipid, implemented in a way to be flexibly used by insane for quick membrane building. Good job! When doing this with real-life cases of new lipids, don’t forget to share your parameters with the community for added impact!

Tools and scripts used in this tutorial

GROMACS(http://www.gromacs.org/)Insane(latest version from the GitHub repo)

References

[1] Wassenaar, T. A., Ingólfsson, H. I., et al. Computational Lipidomics with insane: A Versatile Tool for Generating Custom Membranes for Molecular Simulations (2015) J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 2144–2155. DOI:10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00209

[2] Thermotropic Phase Transitions of Pure Lipids in Model Membranes and Their Modifications by Membrane Proteins, Dr. John R. Silvius, Lipid-Protein Interactions, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1982

[3] Pedersen, K. B., Ingólfsson, H. I., et al. (2025) The Martini 3 Lipidome: Expanded and Refined Parameters Improve Lipid Phase Behavior. ACS Cent. Sci. DOI:10.1021/acscentsci.5c00755

[4] Thallmair, S., Javanainen, M., Fábián, F., Martinez-Seara, H., Marrink, S.J., Nonconverged Constraints Cause Artificial Temperature Gradients in Lipid Bilayer Simulations (2021) J. Phys. Chem. B 125(33), 9537–9546. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c03665

[5] Kilelee, E., Pokorny, Y., Yeaman, M. R., and Bayer, A. S. Lysyl-Phosphatidylglycerol Attenuates Membrane Perturbation Rather than Surface Association of the Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide 6W-RP-1 in a Model Membrane System: Implications for Daptomycin Resistance (2010) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4476–4479. DOI:10.1128/AAC.00191-10

[6] Souza, P. C. T., Alessandri, R., et al. (2021) Martini 3: a general purpose force field for coarse-grained molecular dynamics. Nat. Methods 18, 382–388. DOI: 10.1038/s41592-021-01098-3